by Todd Warfield

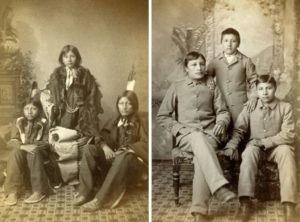

I am a member of the New England Conference Committee on Native American Ministries and as such I get to attend regional meetings. This year, our yearly meeting was held in Carlisle, PA. I knew we were going to tour the Carlisle Barracks, which is where the Carlisle Indian School was in the late 1800’s through early 1900’s. For those who don’t know, Indian boarding schools became a way to deal with the Indian “problem”. In the beginning, Army Lt. Richard Henry Pratt was in charge of 72 Indian prisoners who had been fighting the Army in the southern plains. Pratt transported these Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche and Caddo prisoners halfway across the continent to St. Augustine, Florida. (Ironically, St. Augustine had been the first Spanish settlement in North America.) It was a terrifying experience for the transplanted Indians. The experiment seemed to work. By April 1878, 62 of the younger, more easily educated Indians joined the Hampton Institute in Virginia – a “normal school” or teacher training institute founded by abolitionists for blacks. Pratt’s savage warriors were on their way to becoming teachers. Pratt publicized the success of the experiment through a series of “then-and-now” photos showing the “savage” versus the “civilized” Indians. Pratt coined the phrase “Kill the Indian, save the man”.

Most notable was the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Lt. Pratt convinced parents and tribal elders to send their children by train to a far-off place. Pratt believed this would break the students quicker of their ties to their traditions. Students were prohibited from speaking their native languages. Instead, they were supposed to converse and even think in English. If they were caught “speaking Indian”, they would be severely beaten with a leather belt. Between 1880 and 1902, 25 off-reservation boarding schools were built and 20,000 – 30,000 Native American children went through the system. That was roughly 10 percent of the total Indian population in 1900.

Visiting the grounds at Carlisle was an emotional experience for me. I could feel the presence of those who went here. We toured the Hessian Powder Magazine, a small brick structure, which some Indians were held in solitary confinement. We toured the parade grounds and saw photos of different trade classes from that era. At the end of our tour, we visited the graveyard where some of the Indian children were re-buried from elsewhere on the base. Words cannot properly describe the emotions that washed over me when we were in that graveyard. We had some tobacco to spread and I prayed over several stones.

Andrew Windyboy (Cree) was interviewed back in 2008 and his interview is available on YouTube (https://youtu.be/qDshQTBh5d4). I would recommend watching it to hear the story from someone who went through the school.