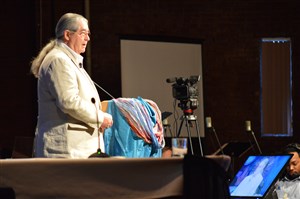

Patricia Warrior Woman Parent, chair New England Conference Committee on Native American Ministries (CONAM), shares this piece on how United Methodists in New England can fulfill our vow at the 2015 Annual Conference to stand with and support our Native American brothers and sisters.

“And so this is Christmas – and what have you done? Another year over, a new one just begun.”

So wrote the late John Lennon many years ago, a question of challenge to the complacent who have, about those who have not. I was thinking of this song as I put together my thoughts for this piece.

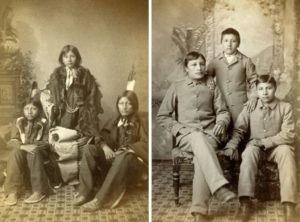

At our 2015 Annual Conference, we repented and made a vow. As a church we asked forgiveness of the Native American community for our collective part in marginalizing them, robbing them of their land, their dignity, their culture and their children. We made a vow to stand with First Nations on issues that concern them, and to stand against the Doctrine of Christian Discovery, a law of our land since John Marshall was Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

One of the problems for us as European descendants is that we are so steeped in our heritage of privilege and “knowing what is best” that we don’t know just how to go about standing with Native people in a way that will build trust instead of adding to the suspicion with which those who came before us are viewed.

How, how, how do we go about this? It takes a lot of time, yes, but it takes something else as well: It takes quietly acting, just doing it, and letting those with whom we stand see us there, asking nothing, and offering ourselves.

We have found some incredible examples in North Dakota recently. If you don’t know about Standing Rock and the Water Protectors, I strongly urge you to check it out and learn all you can.

The world is now meeting there. They have been since summer 2016. The Lakota people stood up and said, “NO!” to big oil when their water supply was threatened by a pipeline that would only supply more oil for sale overseas. They were alone. Yet they stood. And then other Native Nations started arriving. Then other countries around the world. The Conference of the Dakotas decided to honor their vow as well. The world is still at Standing Rock.

On the day that money for Penobscot people from Maine arrived from your New England Conference Committee on Native American Ministries (CONAM) (yes, they are there as well), two cord of wood and 20 yurts from Mongolia arrived as well.

However, the example I want to give to all of us is that of 4,000 veterans; 4,000 veterans who rode buses, drove, and, yes, walked 200 miles to meet at Standing Rock to stand between the people and law enforcement who let loose attack dogs on children and fire hoses on people in freezing weather. They also retrieved stolen canoes and tore down razor wire.

Some of these were veterans of Vietnam, and one of them told the Lakota that he came home from Vietnam knowing shame because of how he was treated. He thanked the Native people for giving him honor.

And one day, the veterans met with the Lakota and took a knee before them. Their spokesman, John Clarke, veteran and son of a veteran, told of how we have taken land, participated in genocide, and still continue to do so, and then he asked for forgiveness and offered them all to be servants of the Native people.

I watched this ceremony, and I wept. THIS is what we all need to do. These veterans, although they have returned to their homes, are ready to go back whenever needed. They didn’t talk about it, they didn’t ask what the Lakota needed – they came. This is our example.

Your CONAM can only give funds to Native Nations in New England, but individuals can find out what is needed at Standing Rock – warm clothes, wood, generators. They are using barbecues – maybe they need briquettes.

And we can find out about issues closer to us by checking out newspaper articles, websites for the local nations, and by asking your CONAM for assistance in getting out and doing. Be there first – and let your actions speak for you – for us.

The old saying goes, “Your talk talks and your walk talks, but your walk talks louder than your talk talks.”

Let’s all get walking.

Aquiene (peace),

Patricia Warrior Woman Parent